310 millions wearable devices sold this year, 2 billion people will be using apps to monitor their bodies, by 2019. Everything can be tracked and measured: heart rate, hours of sleep, food calories, exercise, weight… Yet, the majority of users still struggle to make sense of data and abandon them. We propose novel approaches that get back on the Self in “quantified self” and transform self-tracking in actionable empower.

By Luca Cerina

Research Assistant @ Politecnico di Milano, working on wearable devices and biomed applications at NECSTLab.

The unmet promise

In the recent years, the market for self-tracking apps and wearable devices skyrocketed, with industries and media sharing promises of Health and Wellness waiting just a click away from us, preaching the advent of data-sharing products that will solve all our health problems. However, the reality depicts a different situation: most of the health apps fail in disuse after a few months, users struggle to understand the numbers, the graphs, and the amount of data that is collected from them (even unconsciously) and feel inadequate in this model that fails to engage.

Although the industrial players focused on the “biomedicalization” of health, the exponential scaling of their market, the collection and the stockpiling of what is called the New Oil, in the end no one really knew what to do with all this data. In fact, the real value of data is not given by its accumulation (like oil or gold), but from what it can be done on it: the extraction of information and the generation of insights, the sharing and the transfer of it and most importantly, the actions that can be performed upon data.

Me, the imperfect self

To resolve this knot, we believe that it will be necessary to shift back from the Big Data approach that spans thousands of users, smoothing the details and the uniqueness of the single person, to methods and technologies that focus on the personal behaviour or the activity of small groups of people with common goals. That’s because human life means imperfection, we forget to insert data into an app or wear a device, we suddenly change our lives after an event (like an injury), we can be fallible in the adoption of a new habit or lie about our adherence to it, and we can feel unmotivated if the latest lifestyle app does not keep her promises.

In this messy scenario, new algorithms should be written to compromise with our faulty self, find a clue in our personal data without necessarily having to compare it with an enormous and anonymous population, and always engage us with positive feedbacks instead of judging our inadequacies.

Switching to action

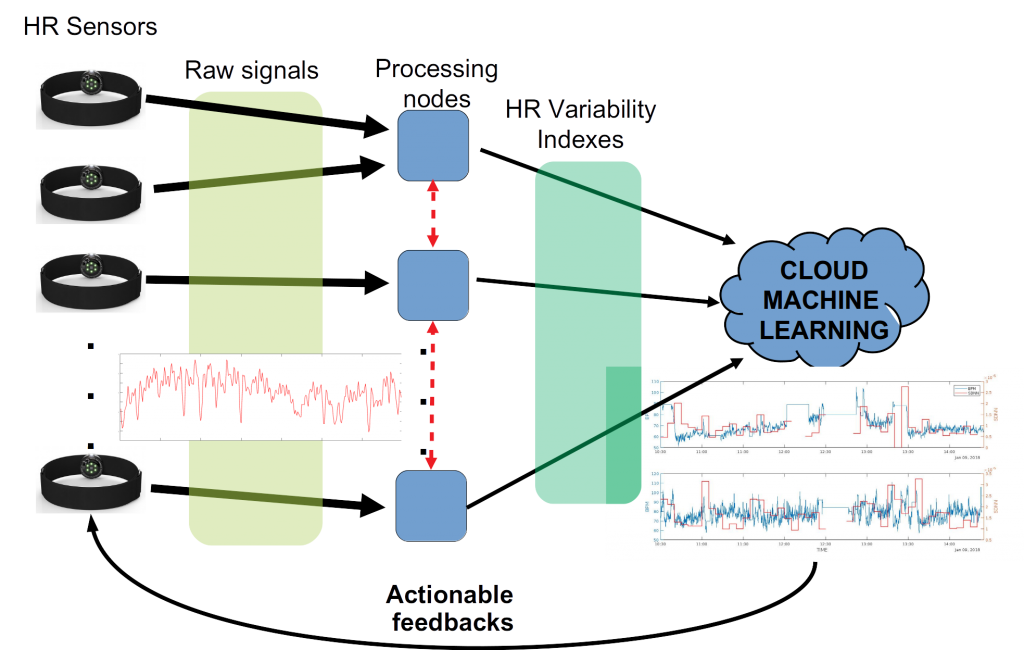

In order to resolve this problem, we are tackling it from multiple fronts. The first one regards apps and devices that guarantee the best measure quality (e.g. accurate heart rate) and we try to mitigate the burden of data collection on the user. We are designing a hub that collects data from user-worn devices in an ambient, without any interaction from them.

Subsequently, other research projects try to transform raw data into information using domain-driven machine-learning tools and methodologies that are able to deal with missing or noisy values. For instance, the amount of hours slept in one night are almost useless, while their fragmentation (light/deep sleep phases) and the single night against the preceding ones could provide more information and a hint on how to improve user’s sleep.

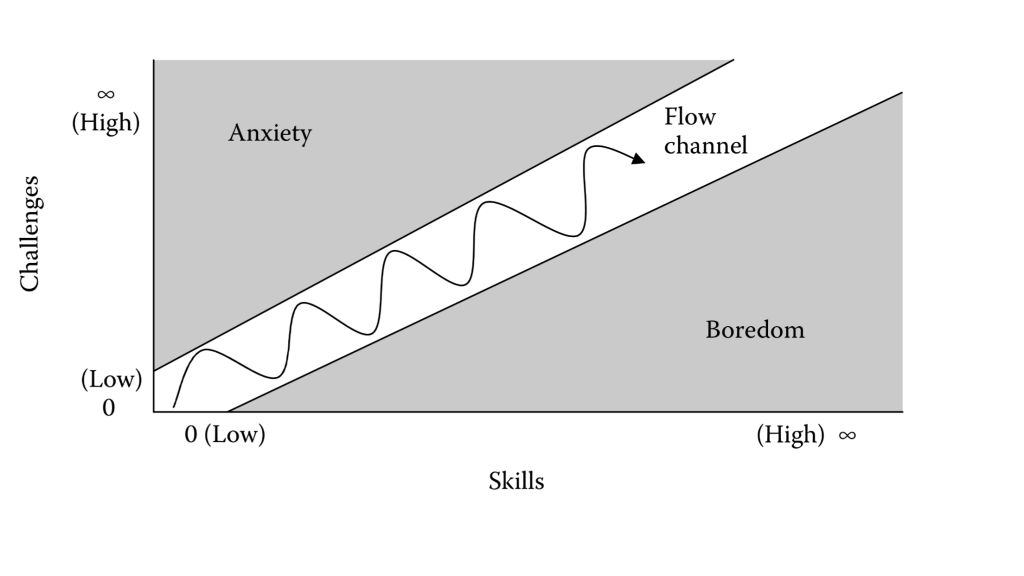

Finally, we step into action. All our methods are goal-driven by design (e.g. losing weights, moving more), because if we can measure a goodness of fit, the distance between the measure and the goal, and its evolution, we can provide adaptive feedbacks to the user at its own pace while the algorithms try to understand the causes of a sudden slump in the progress. Furthermore, we take inspiration from the flow paradigm of game design and measure the user’s effort: if the challenge is too low with respect to the user skills, it gets boring and the user stops, if it is too challenging, the user gets frustrated and stops; hence we need to keep the users “in the flow”.

We believe that the synergy of these methods could represent a revolutionary approach to health apps and devices, from consumers’ one to novel implications for translational medicine.